At the end of May I

scouted a possible location for an astro shoot in the Allgäu mountains come next new moon. A good milky way photos lives and dies by the foreground and I wanted somewhere with a good view over the alps. The middle of June arrived and the forecast for Friday and Saturday was awful; clouds, rain, the lot. Nothing doing. The next weather window was going to be Tuesday night. To make matters worse, the initiator of the whole idea - my friend Matthias - couldn't make it as he was stuck up at work in northern Bavaria. But an old school friend who happens to live in Munich was interested enough to bite when I announced my intentions on Facebook and so Martin and I ended up heading down to Fischen im Allgäu early Tuesday evening to see what we could see. Meteorologically we were on a rising tide - there were still some clouds around but the weather was definitely clearing from the north and so we were optimistic.

The Shoot

|

| Waiting For The Moon To Set || Huawei P30 Pro |

Dusk

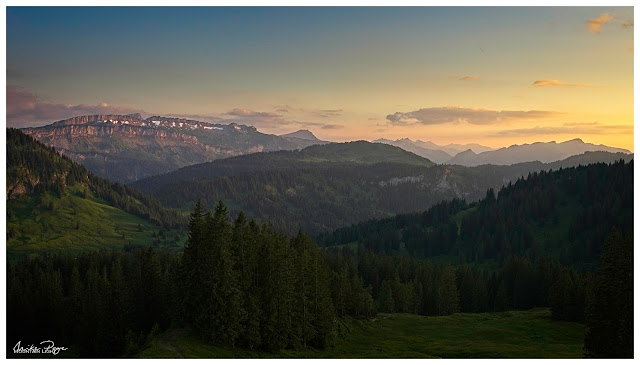

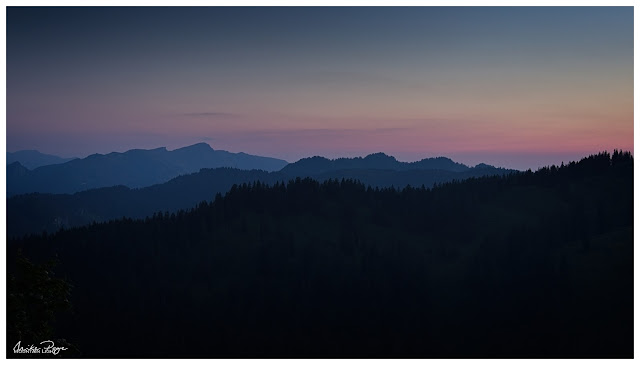

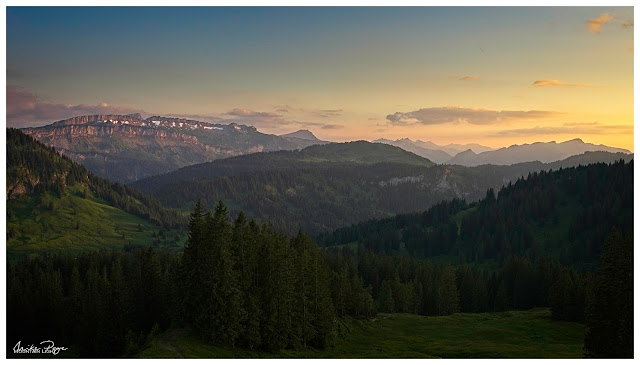

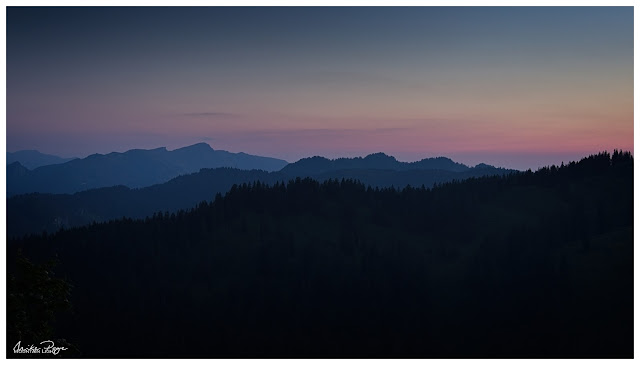

Driving down there were still cloud remnants lurking in all the wrong places, but the northerly wind was driving them deeper into the alps and so we weren't too concerned. We set off from the car-park in the early evening light. Normally, like most people, I spend most of my time in the mountains during the day. Unless I'm staying in one of the mountain huts, I'm generally back down in the valley for dinner. This evening's experience may get me to revisit that schedule. There's a good reason why landscape photographers choose to shoot at the ends of the day; the light quality is very different. It's softer, gentler and less blue. Watching the pastel colours changing on the Vorarlberg mountains in the gathering dusk made me start rethinking how I plan my days in the Alps.

|

| As the Sun Goes Down || Olympus f/7.1, 1/80 s, ISO 200 |

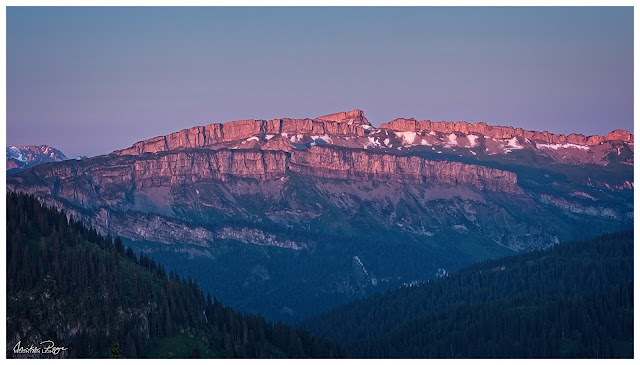

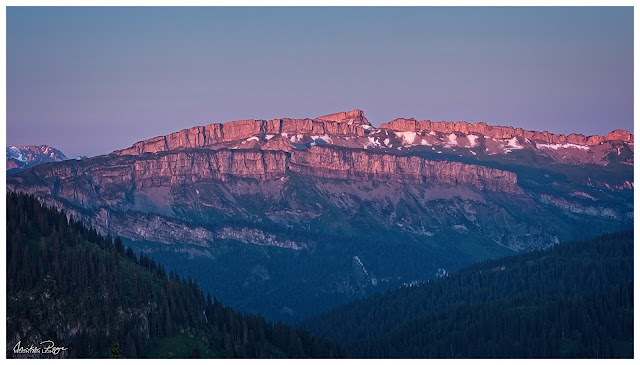

It was great to see that not all of the snow had disappeared in the intervening weeks; I find the last snowfields really make a photo like this and I don't shy back from exaggerating them in post-processing like here (above).

|

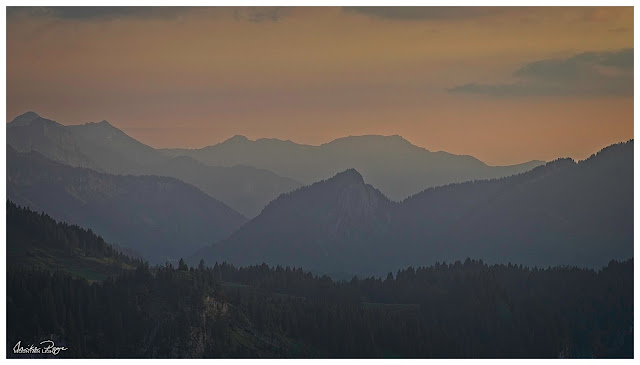

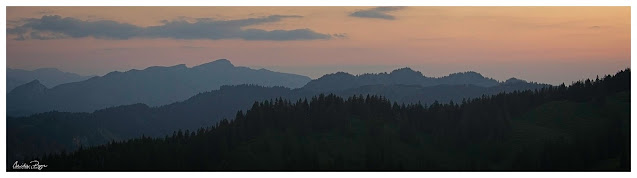

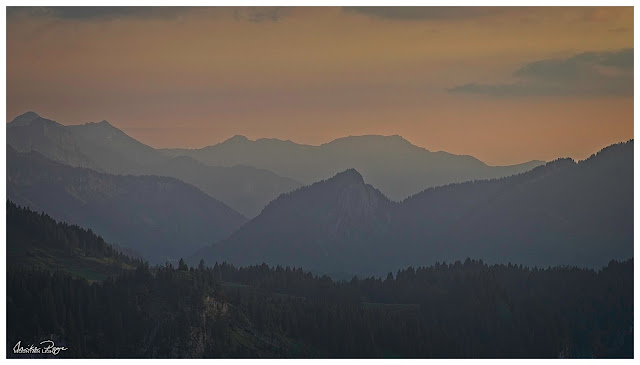

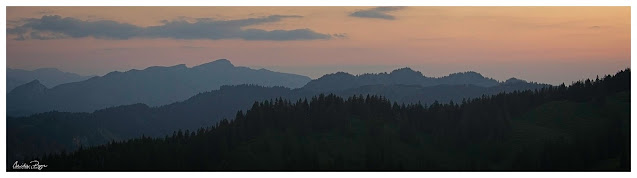

| The Pastel Colours of Evening || Olympus f/7.1, 1/160 s, ISO 200 |

|

| All the Layers || Olympus f/7.1, 1/30 s, ISO 200 |

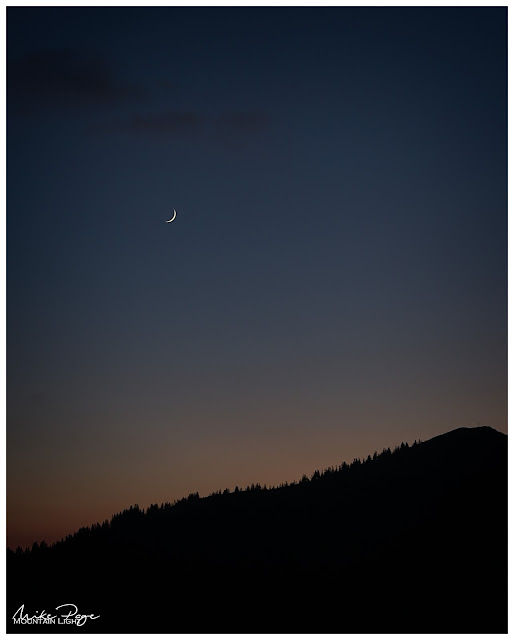

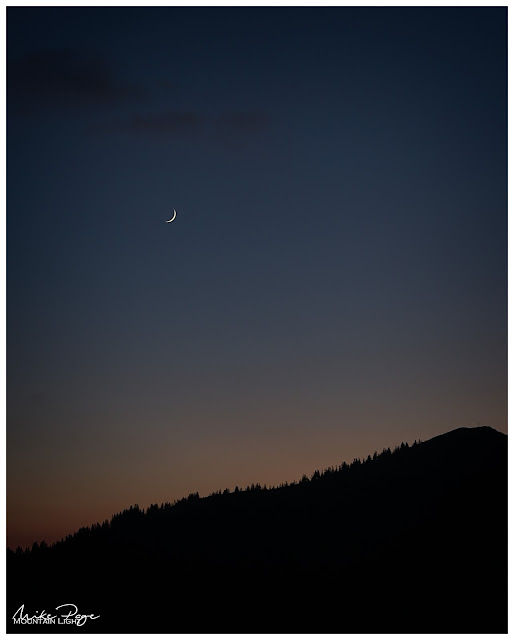

Moonset

I'd promised my school chum a relatively easy hike up to the first mountain top that I'd identified. Unfortunately we didn't make it all the way and ended up about 100 m below the summit on a slight shoulder. The location was optimal for the first spectacle of the evening - the fresh new moon was due to set behind the peak above us and our location appeared to be optimal for that. My smartphone app (Sky View) was showing me where the moon should be in the sky, but for the life of me I couldn't find it. I was beginning to fret that either (a) the app was playing up, or (b) there wasn't going to be enough moon to see. As the sky darkened and I still couldn't see it Martin spotted it - why we hadn't seen it before was a complete mystery as it was so clear at this point.

|

| Well It's Obvious Now! || Olympus f/8, 1/5 s, ISO 200 |

|

| Setting Moon || Olympus 100 mm f/5.6, 0.6 s, ISO 400 |

Before we turned our attention to the stars that were beginning to appear in twos and threes there was one more dusk photo to grab before the technical stuff began:

|

| When Purple Comes Out To Play || Olympus f/5.6, 40 s, ISO 200 |

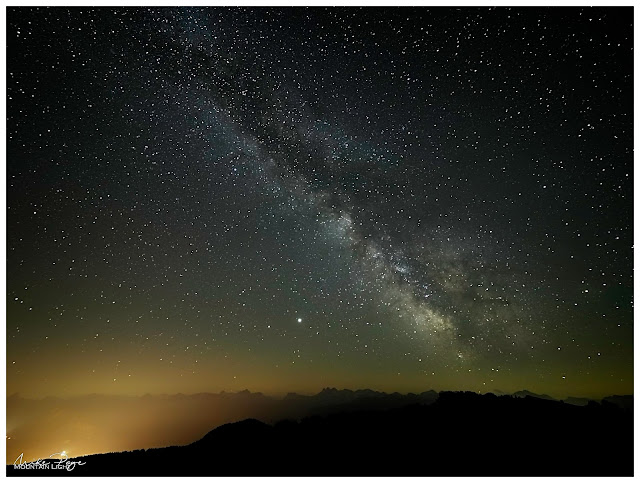

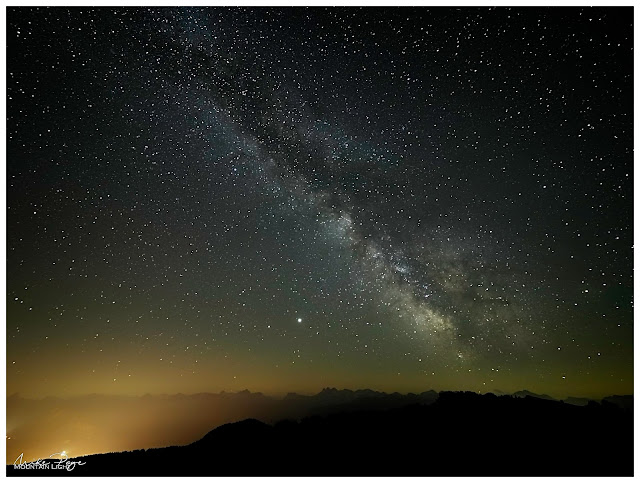

As fun as it was to shoot the setting moon, it cost me my first milky way shots as I wasn't set up to get a good foreground photo during the blue hour that I could use to blend into the final image in post. The shot I ended up getting was ok, probably one of my better photos of the Milky Way per se, but the foreground is lacklustre. I don't know whether it would have been any better 100 m higher up either, but the lesson is that you need to be in position early, you need to get your foreground shots in in good time and you can only recon on about two good astro shots per night, one after the sun goes down and one before it rises, unless you're shooting with multiple cameras.

|

| Collision Imminent || Olympus 300 mm f/5.6, 0.6 s, ISO 1600, Composite Image |

Milky Way

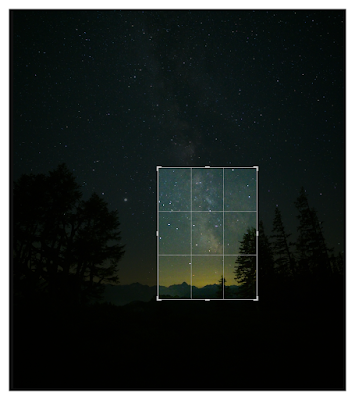

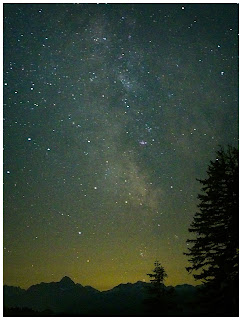

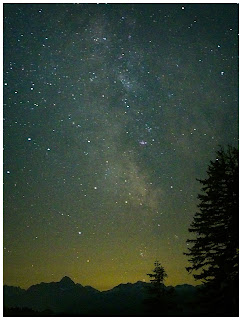

The challenge with astrophography is the low light levels. You need an open aperture and relatively high ISO with a wide angle lens to get enough light to the sensor before the earth's rotation turns the star points into lines - the so-called star trails. As a rule of thumb, the maximum exposure time before this happens is 500/focal length* (400 if you're being conservative). So for my 16 mm equivalent wide angle lens, I can shoot for 25 s. In order to further increase light-sensitivity, we need to increase the ISO. Small sensor cameras (I shoot with an Olympus micro four-thirds crop sensor, technically a small sensor camera) are notorious for being sensitive to high ISO, the images tend to have a lot of unsightly noise - a random phenomenon that causes an unsightly buzz in the image. But being random, there's a solution: If you take multiple shots and then take the average of those shots, the noise is diminished. The challenge is that the software performing the calculations needs to take into account the fact that the stars are moving - if it didn't you'd end up with the trails again. All in all quite a technical feat, especially when there's a foreground involved. Fortunately the free Windows software Sequator can do all of this - it's what it was written for. It's not the most user-friendly app, but if you know what you're doing (or in my case if you know someone who knows what they're doing), it's extremely powerful. The trick seems to be not using too many of the features, but more of that below.

*25 mm equivalent, so with my micro four-thirds sensor I need to double my focal length

|

| First Starlight - Stacked but Unprocessed || Olympus 8 mm, f/2.8, 25 s, ISO 6400, Stacked |

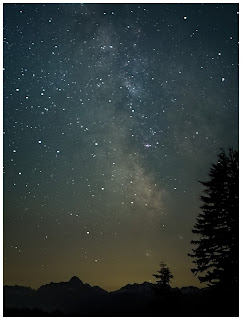

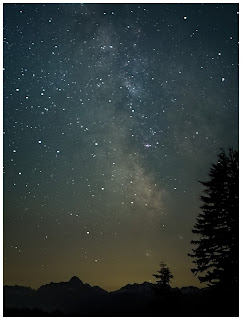

We could just about make out the trail of the Milky Way in the Allgäu sky. From our vantage point I tried several series of shots, with and without my Haida Clear Light filter and Tiffen Fog filter and with the new 7Artisans 7.5 mm fish-eye. In the end I liked the unfiltered images through the Panasonic Leica 8-18 mm the best. The above image is stacked to reduce noise but otherwise unprocessed. The sheer clarity of the image just blows me away. The detail in the Milky Way is amazing. But I don't think this is a good Milky Way photo. It's a good photo of the Milky Way, but like I said earlier, a good Milky Way photo stands or falls by the foreground and I wasn't satisfied with what I was getting here, so after a cup of tea and a pasty (thanks Martin, those were life-savers) I lay down for a 45 min shut-eye before heading up to the ridge, where I knew just the spot.

|

| With Haido Clear Sky Filter, Unprocessed |

|

| 7Artisans 7.5 mm Fish-eye Lens, Unprocessed |

One of the greatest challenges with astro photography is finding infinity on the focus dial. Looking through the viewfinder you're confronted with an almost completely black image - finding something to focus on can be extremely difficult. If there's a bright light a couple of miles off this works relatively well, as at this distance there's effectively no focal change between 2 miles and infinity. It was quite a challenge in the dark though, and I had to hunt through the magnified viewfinder on the Olympus to locate Jupiter (bright spot in the middle of the images above) and twiddle the focus ring of the lens to render the tiny fuzzy light as tight and small as possible. Then it's shoot and hope. You can examine the images on the camera display, but you're never entirely sure whether your photo is sharp or not until you get the image on the computer screen.

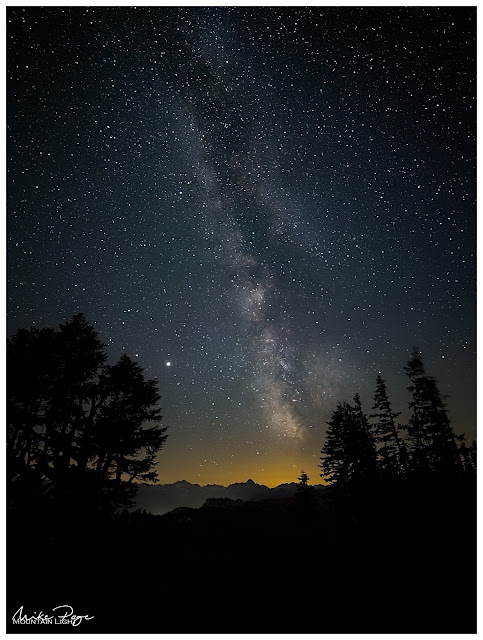

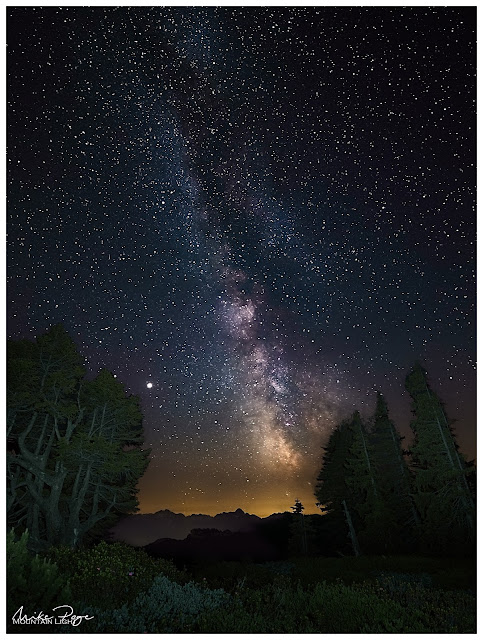

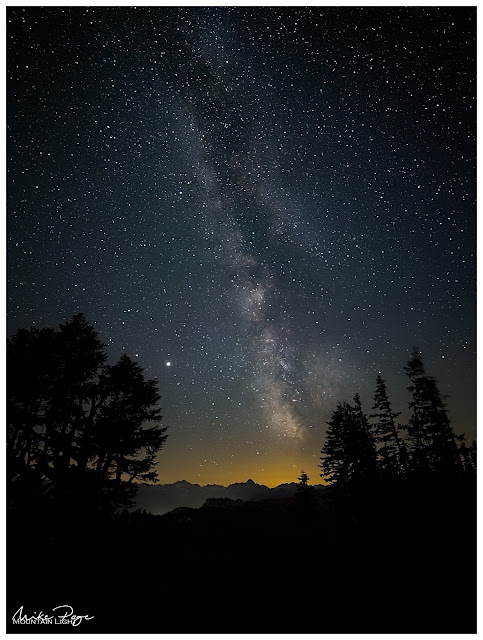

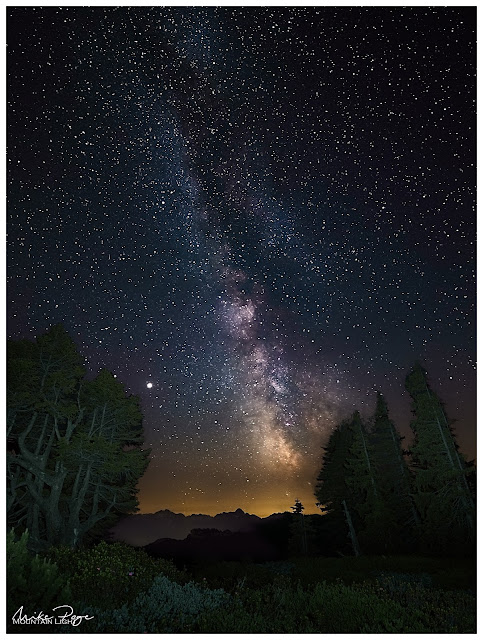

Despite being pitch dark, it was easy enough to find my way by the light of my head-torch, having scouted the area less than a month before. I located the second spot relatively easily and set up the tripod again. A few ultra-high-ISO shots helped me frame the photo correctly. I also tried some low ISO long exposures with a bit of light painting so that I would have a foreground to go with it. This is a separate image that is blended with the processed astro image in post processing (see last image). This final photo here has to be my favourite image of the year so far. I didn't get a huge number of finished shots that I was happy with, but at the end of the day, if you come away with at least one, that's a win.

|

| Milky Way Over The Allgäu || Olympus 8 mm, f/2.8, 25 s ISO 6400, Stacked |

I carried on shooting for a while after this into the blue light of pre-dawn before giving up and catching a few more minutes sleep lent against my rucksack. It was a mild night with little wind and the ground was comfortable and dry beneath me, not a sound to be heard.

Birdsong and a yipping fox in the valley below alerted me to the coming dawn. By the light of the red band of cloud to the east I could just make out a small peat pond nearby that I'd just avoided in the dark. In retrospect I should have taken a lower vantage point for this shot. This is two images blended in ON1 Photo Raw, one for the sky, one for the foreground. I took the liberty of brightening the tufts of cotton grass to emphasise them in the pre-dawn light.

|

| Mountain Tarn at Dawn || Olympus f/5.6, 1/6 s, ISO 200 |

Then it was down to find Martin and head down to the car. I found him warming himself over his camping stove and ready to return to the valley. As I waited for him to pack his things there was time for one last shot of the sun rising on the mountain escarpment opposite us.

|

| The Red Light Of Dawn || Olympus f/5.6, 1/30 s, ISO 200 |

Processing the Images

If you're not interested in the nitty-gritty of processing astro photography you can probably stop reading here and scan to the last images. It's very easy to over-process Milky Way photos: I spent two evenings working on this last shot only to have Sharon (correctly) tell me that it was too speckled and she didn't like the foreground. I've left this technical bit to the end for my techie friends who'll be interested in this stuff (hi Matthias!).

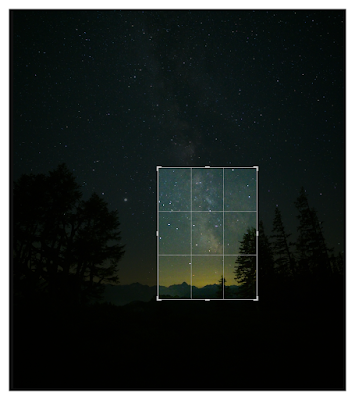

Before the images can be 'stacked' (averaged), they need to be in tiff format. ON1 Photo Raw, my post-processing software can export tiffs, but they're the wrong format for my stacking software, Sequator. The images have to be opened in Olympus Workspace and exported as tiffs from there. For each image I used 10 star images and two control images with the lens cap on (lights and darks respectively).

|

| Crop of main image |

|  |

|

| Unprocessed image OOC | Stacked in Sequator

10 Star images, 2 Noise images (with lens cap on), Align stars, Freeze ground, Sky region: Partial, otherwise all default settings | Processed in ON1 Photo Raw 2020

Develop:

Contrast +24, Highlights +18, Midtones +15, Shadows -20, Whites +45, Temperature +40, Tint -3

Effects:

Sharpening, Noise Reduction (Moderate), Tone Enhancer (Shadows Lighter on foreground; Midtone Contrast Boost, 50%), LUTs (1983, 35%), Sunshine (Sunglow, 50%), Curves (mild S-curve), Dynamic contrast on Milky Way

|

I also tried a blend of my favourite image with the light-painted foreground in ON1 Photo Raw. It's not perfect as I seem to have adjusted the camera between frames and had to stretch the resulting images to fit. I'd be interested to hear which image you prefer, this one with more detail in the foreground trees, or the original "Milky Way Over The Allgäu" above. My jury is still out on this one.

|

Milky Way Over The Allgäu II || Olympus 8 mm, f/2.8, 25 s ISO 6400, Stacked and Blended

|