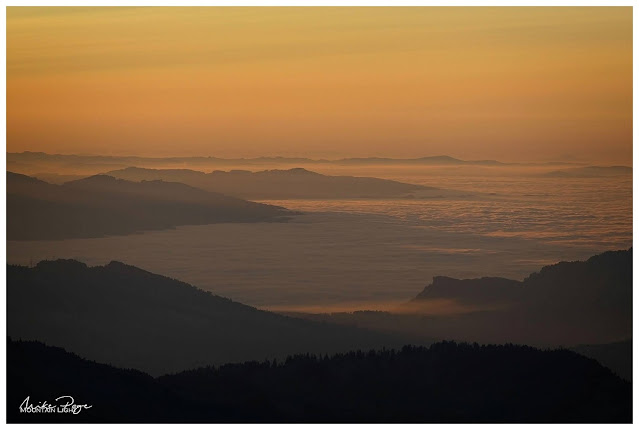

Matthias' message warning me that the forecast was set for sensational sunsets at the weekend reached me on Thursday evening. At the same time he informed me that he was waiting for confirmation that he hadn't been infected by a colleague and so we'd have to play it by ear. In the meantime: where to go to catch the spectacle? I immediately recalled a tour that we'd done as a family earlier in the year in the western Allgäu mountains and where we'd had an uninterrupted view towards the Säntis in the north-eastern corner of Switzerland.

|

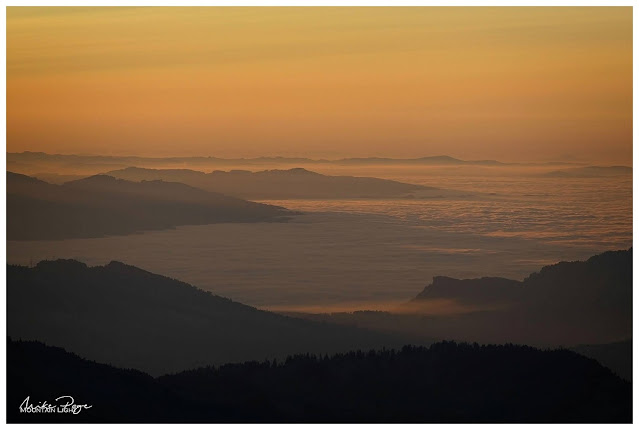

Cloud Inversion over Lake Constance || Olympus 100 mm, f/8, 1/100 s, ISO 200

|

|

Looking through our hiking book for the Allgäu, Sharon found a suitable looking tour just north of our previous jaunt, involving the summit of the Hochgrat. Looking it up online, I noticed that they had a cable car up to a few meters below the summit with a mountain restaurant and that they were advertising late opening due to the full-moon. Slowly a plan was forming in my mind involving an epic sunset shoot followed by some cool blue-hour photos by moonlight.

By Saturday morning, Matthias still hadn't received the all-clear, so we reluctantly decided that we would be better off going our separate ways this time - a decision that I don't think either of us regret given the images we were able to capture. Given the fact that we were planning a relatively late shoot, we weren't in a hurry to leave on Saturday morning.

|

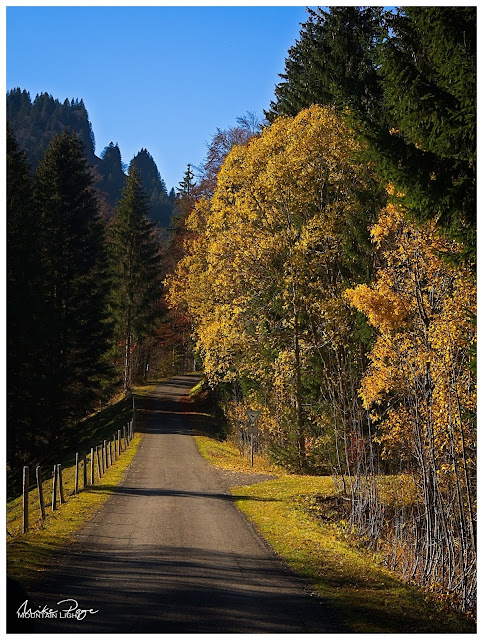

| Into the Aubach Valley || Olympus 44 mm, f/8, 1/160 s, ISO 200 |

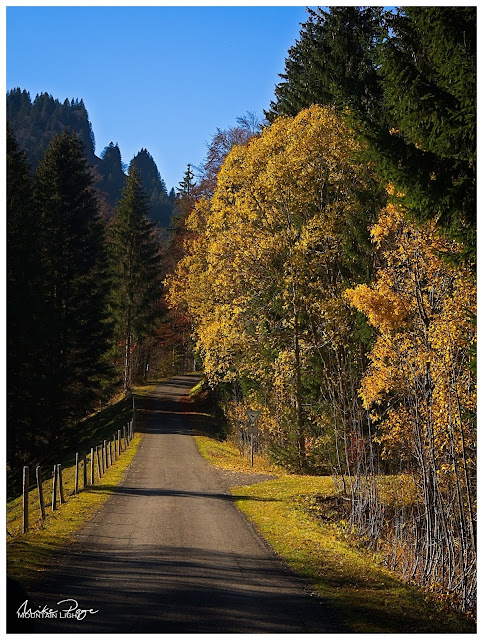

We'd planned to park well up the Aubach valley at the Alpe Scheidwang, but after having have to wait for a small herd of cows to be ushered down to their winter quarters (the Alpine 'Almabtrieb' tradition - usually quite a photogenic event) we drove up to the bottom of the toll road to find it closed for the winter already. This put 8 km (5 miles) onto both ends of the walk, but we weren't going to be put off so easily.

The Aubach valley is delightful and full of deciduous trees. Unfortunately we were a few weeks too late for the best colour ('peak fall'), but we were still treated to a few last silver birches glowing golden in the afternoon sun. The polarising filter really brought out the sky's colour, bringing the cirrus clouds drifting overhead into stark relief.

|

| Golden Silver Birch || Olympus 12 mm, f/6.3, 1/125 s, ISO 200 |

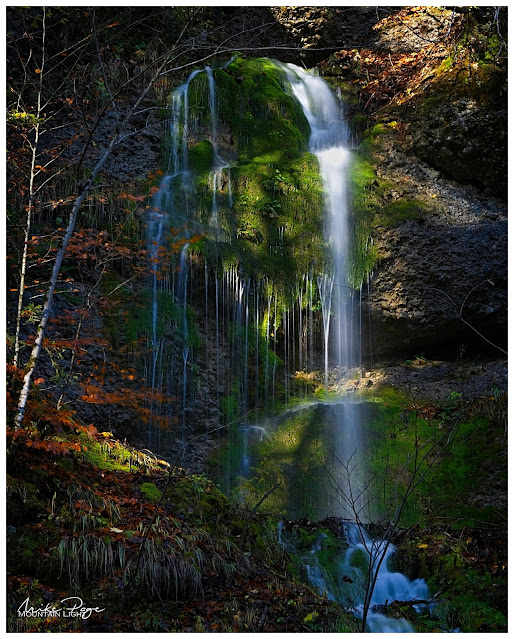

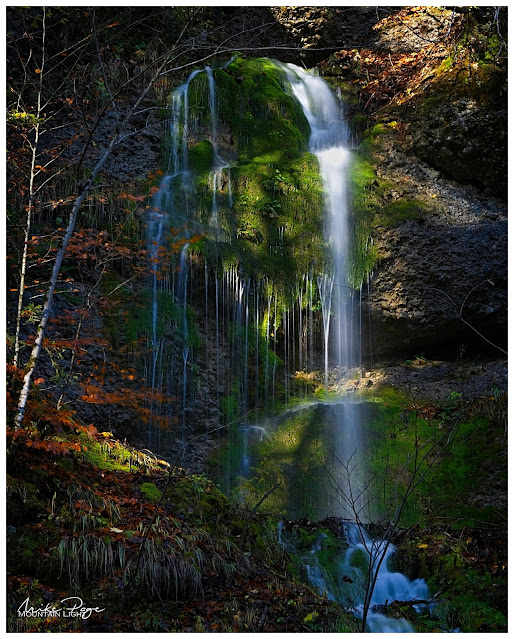

The unexpected extra mileage meant that we didn't have much time to enjoy the valley, but there are a number of waterfalls left and right of the trail that would warrant a more leisurely investigation another time under the right conditions. The live ND function on the new Olympus makes shots like this child's play (if you can find them that it). The on-board computer can simulate a 5-stop light reduction.

|

| Roadside Waterfall || Olympus 61 mm, f/8, 1 s, ISO 200 |

One of the Olympus features that caught my attention and caused me to opt for this system over say those of Fuji, Sony, Canon or Nikon was the image stabilisation - an exceedingly clever system that compensates the movement of the photographer and enables you to still get remarkably sharp photos. The shot above, for example, is a 1 s exposure. As a rule of thumb, without any stabilisation (unless you have a really steady hand) is that the shutter speed shouldn't exceed 1/focal length (e.g. 1/50 s for a 50 mm lens). Being able to take shots like this hand-held is a huge advantage. Add to that the brand new in-camera ND filter (neutral density - a darkened filter that is pure grey) and you've got a winner. The Olympus E-M1X had this and so does the new E-M1 Mk III, of which I have been a very happy owner for about a month now.

Climbing out of the valley towards the ridge and our destination - the 1834 m high Hochgrat - the snowy tops of the inner-Alpine peaks began to show themselves. The previous morning there had been snow even on the northern edge of the Alps and there were signs of fresh snow, but they quickly disappeared over the course of the day. As we climbed out of the valley and could peer over the edge we could see that the main Alps hadn't shed their white blanket so easily.

|

| Peeking Over The Edge || Olympus |

As we climbed towards the ridge, it wasn't only more mountains that we could see, but more people as well. There's a cable car that runs up to a point about 80 m below the summit starting near the town of Oberstaufen on the other side of the mountain to where we started from. Due to the full moon, the cable car was running until 21.00 and a lot of people were understandably making the most of the last Saturday before the renewed lockdown to tank up on fresh air.

Catching the Sunset

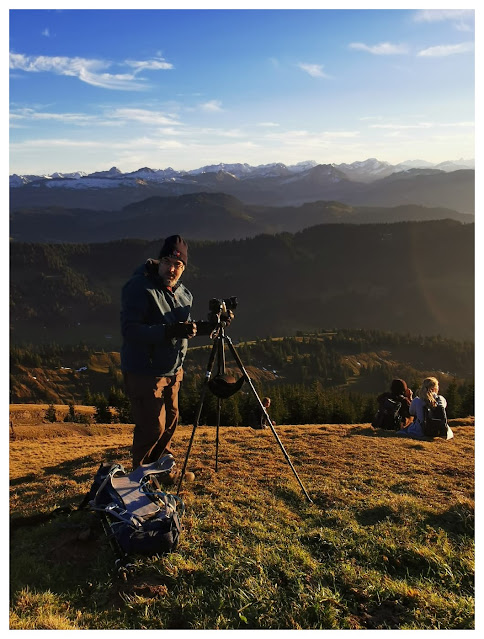

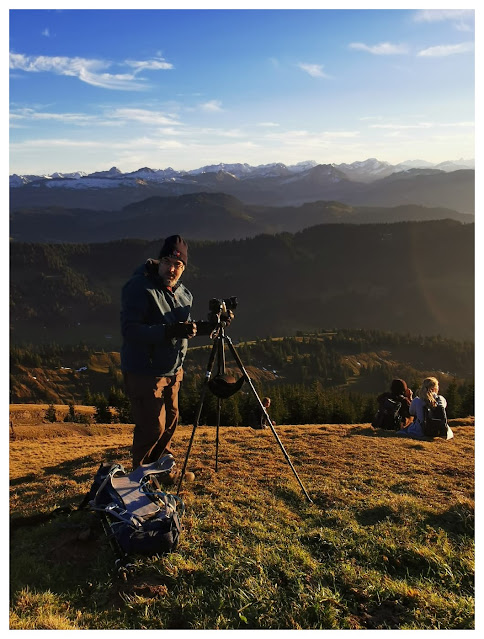

Despite the larg(ish) numbers of people, there was plenty of room on the summit to settle, grab a snack and wait for the ensuing spectacle. There wasn't as much high cloud as there had been the previous evening, but the remnants of cirrus clouds, particularly on the western horizon, gave us hope. Although I'd deliberately chosen a spot on the very edge of the summit and demonstrably got my tripod out and ready, it didn't stop another photographer from setting up between us and the sunset. To be fair, he probably hadn't noticed me - my tripod was out but not extended, but it still left me fuming at him (silently of course, I am British after all) and so I demonstrably set up just left of him as we waited for the show to start.

|

| Waiting for Sunset || Credit: Sharon Page, Huawei p30 Pro |

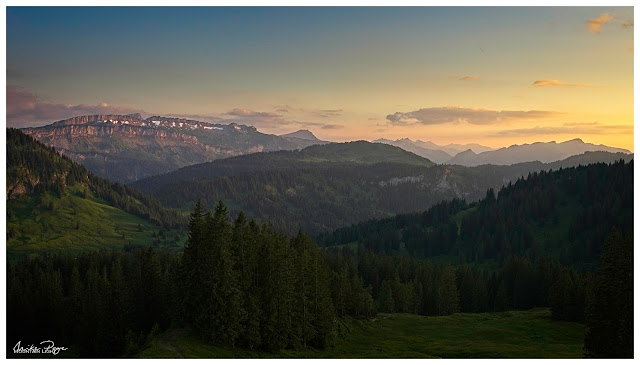

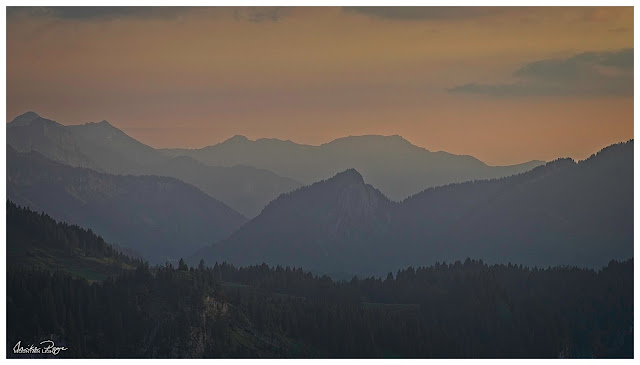

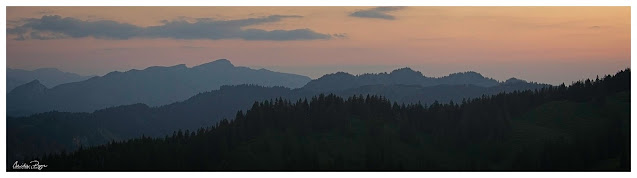

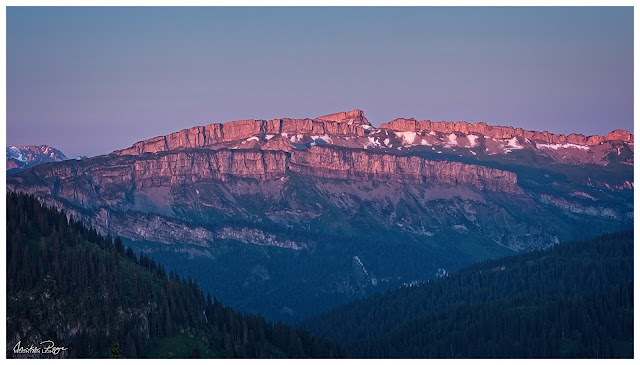

As well as the main view in front of us, the slowly setting sun was beginning to light up the bigger mountains of the Allgäu in a very alluring fashion. Taking panoramas like this I'm always torn between the bigger picture and detailed shots of individual mountains and larger panorama shots. I must have swapped between the 12-100 mm and 8-18 mm lenses half a dozen times as the evening progressed, depending on how the fancy took me.

|

| Alps at Sunset || Olympus 38 mm, f/8, 1/500 s, ISO 200 |

|

| Hochvogel - Matterhorn of the Allgäu Mountains || Olympus 75 mm, f/8, 1/50 s, ISO 200 |

Then it was just a question of waiting. Exposing sunset photos is far from easy. Either you get a well-exposed foreground and a pale sky with a burnt-out spot where the sun should be, or a dark foreground and a brilliant sky. Working with a tripod it was relatively easy to take multiple exposures of each shot and put them together afterwards in ON1 Photo Raw. This is necessary because our cameras are not as good at resolving the range of bright to dark as the human eye is. Normally when I'm 'exposure bracketing', I'll set the camera to 1/4 and 4x the light (two stops under and two stops over), this time two stops wasn't going to do it and so I went to three (1/8 and 8x the light) and even then it was borderline shooting directly into the sun.

|

| Sunset with the Crowds || Olympus 18 mm, f/8, 1/100 s, ISO 200 |

Even with these precautions, the sun was almost too bright for the camera as it dipped behind the Säntis.

|

| Sunset over the Säntis || Olympus 100 mm, f/8, 1/125 s, ISO 200 |

|

| Hardly Alone || Credit: Sharon Page |

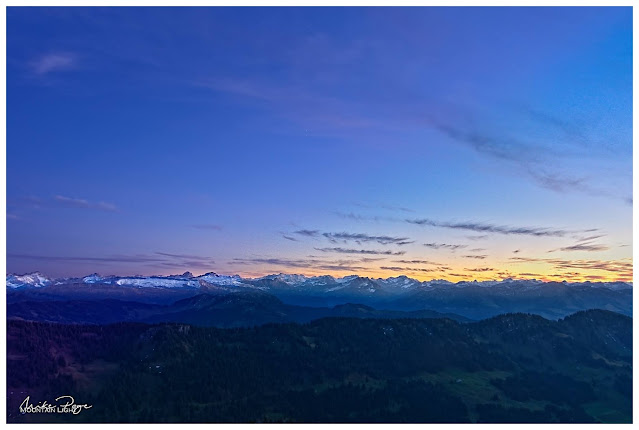

Always Wait for the Encore

About 18 years ago, the band Blackmore's Night was playing one of the local concert venues. The eponymous Richie Blackmore was the one-time lead guitarist of two of our favourite bands (you may have heard of them; Deep Purple and Rainbow 😉). The newer music style of Blackmore's Night is a bit twee and wasn't really worth hanging around for the encore for, so in order to beet the rush for the car-park (and keep the babysitter's fee to a sensible level) I suggested that we cut out early. We were just walking across the road when I heard the opening chords of "

Difficult to Cure" - Rainbow's rock adaptation of Beethoven's 9th and one of my favourite tracks of theirs. The hairs immediately stood up on the back of my neck and we did a

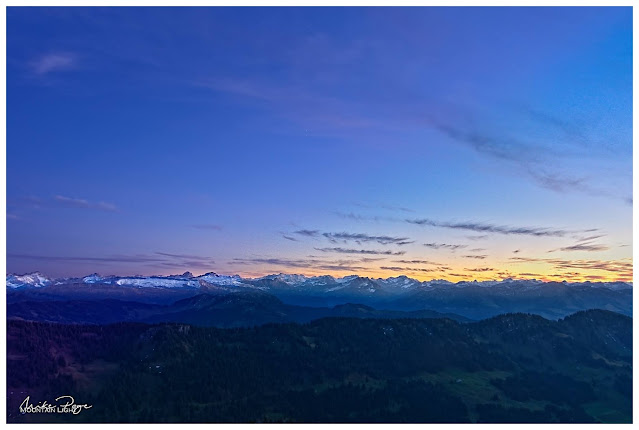

volte face and marched back into the courtyard to enjoy a great rendition of this rock classic. Why am I telling you this? Well the moral of the story is that as with concerts, when photographing sunsets, you should always wait for the encore. Once the sun dips below the horizon, it lights up the clouds from below leaving you with the classic breath-taking oranges, reds and purples - and yes, sometimes even

deep purples.

|

| Always Wait for the Encore || Olympus 25 mm, f/8, 1/50 s, ISO 200 |

Another good tip for photography in general is that you should always look over your shoulder for the unexpected scene. Despite wanting to get to the restaurant before the crowds did - we knew that we were going to be around for a while yet for the blue-hour - we spent a couple of minutes scouting the area for some last shots before setting off down the path to the top of the cable car to grab some well-deserved chow. I've had better food in the mountains, but sitting outside on the terrace of the restaurant I don't think I've had many better locations.

|

| And Keep An Eye Over Your Shoulder || Olympus 75 mm, f/8, 1/50 s, ISO 200 |

|

| Friends || Olympus 75 mm, f/8, 1/30 s, ISO 200 |

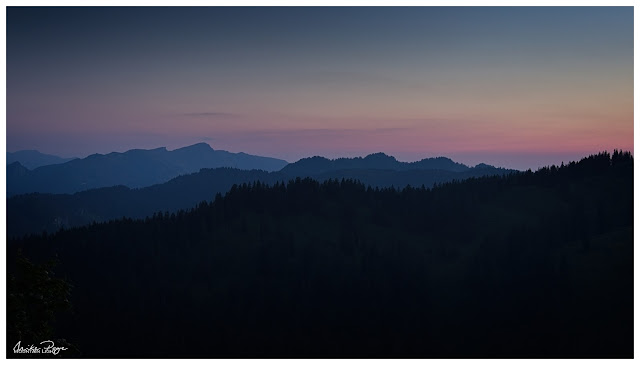

On to the Blue Hour

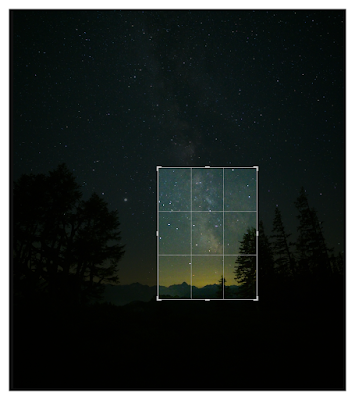

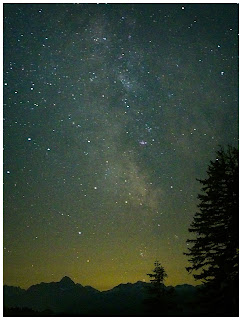

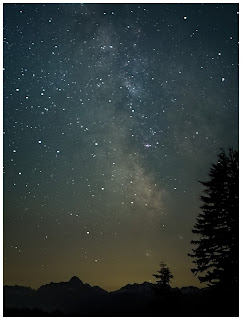

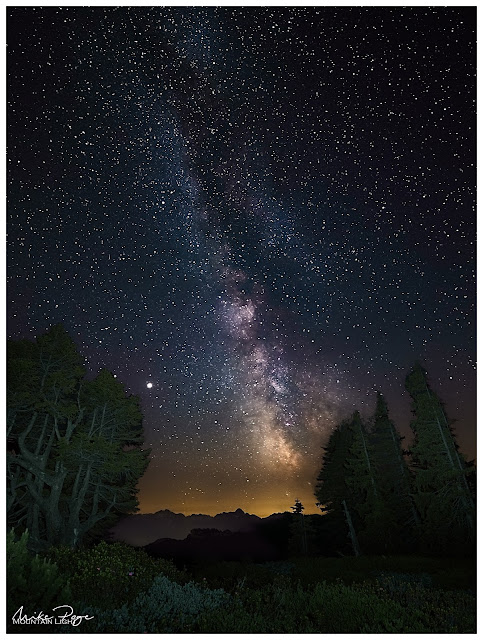

As we polished off our venison goulash on the terrace overlooking the valley, or Käsespätzle in Rhi's case, the lights started to come on, both in the valley and above us. I absolutely love blue hour photography. Since my stint in the Allgäu shooting the Milky Way back in June, I've become an ardent fan of this time of day. Every photographer has their favourite light. For some it's the hour before sunrise, when lakes are still mirrors and mist hangs in the valleys, for others it's the golden hour, that time just after sunrise or just before sunset when the light turns that gorgeous colour, illuminating subjects gently from the side. Mine is the evening blue hour, catching the sky as it turns pastel shades of yellow to purple. If I'm in the mountains, and even better, if there's fresh snow on the peaks, then I'm in heaven. I was in heaven:

|

| Photographer's Delight || Olympus 12 mm, f/8, 0.6 s, ISO 200 |

Not only was the view to the south hotting up (above), the lights were beginning to show in the valley. Dusk photography is always fun - you invariably end up getting details on the photos that the native eye didn't spot. Although the eye has a greater dynamic range than the camera sensor, the sensor is more sensitive to low levels of light, especially if you keep the shutter open for a few seconds as here. I never noticed The Plough when I was taking this photo, but it's staring you in the face here.

|

| The Plough over Oberstaufen || Olympus 10 mm, f/3.1, 30 s, ISO 200 |

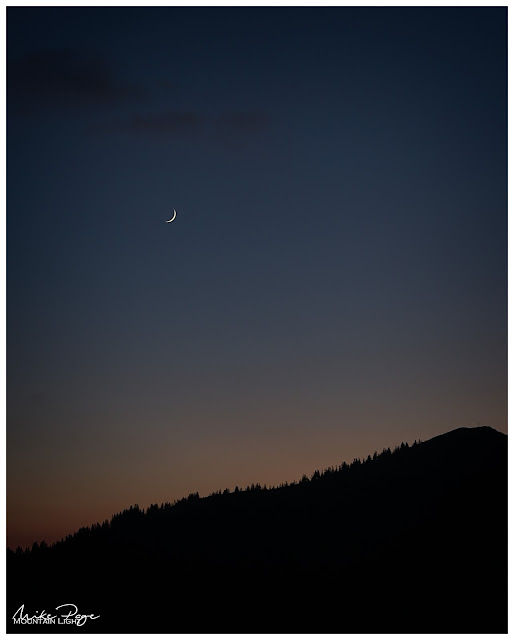

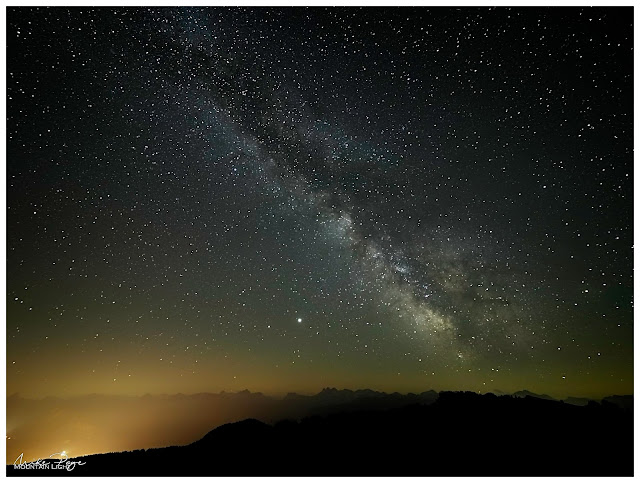

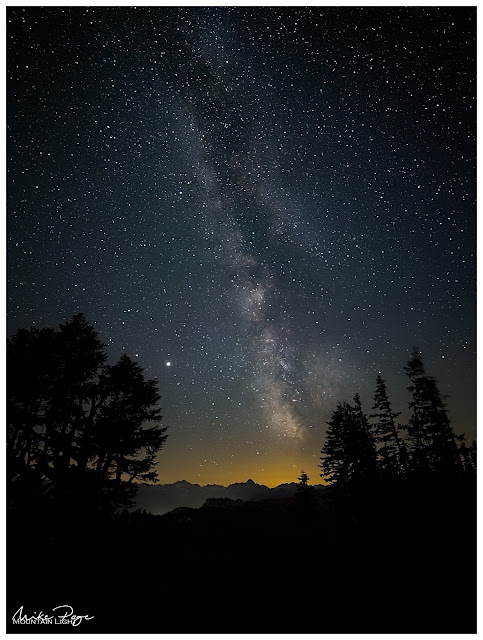

But the sunset wasn't the only heavenly spectacle that the evening had prepared for us, we still had the full moon to go. It was low on the eastern horizon as we started off on our three hour trek back to the car. I tried a couple of shots, but couldn't get the focus properly - always a problem with low light photography. Yes, yes, I know the Mk III has the super-duper star AF mode, but in my rush I completely forgot about that, and wouldn't have known where to find it in the dark even if I had. On top of several expertly exposed shots that would have looked brilliant if I'd got the focus right, I managed to squeeze this last shot off my focusing on Mars.

|

| Allgäu by the Light of the Moon || Olympus 9 mm, f/3, 30 s, ISO 800 |

The moon was so bright that we didn't even need the head torches that we'd brought with us. The long yomp along the Aubach really dragged on the way back, leading Rhiannon (girl-child) to issue the warning "the photos better be worth it!". I'll leave you to be the judge.

Oh, and Matthias tested negative.